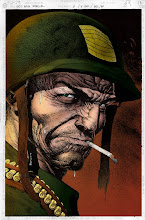

Patrick Henry's "Treason" speech before the House of Burgesses in an 1851 painting by Peter F. Rothermel

In honor of the 2008 Presidential Primaries I thought I'd post what I consider to be great speeches from American history. I got this idea from

Washington Post.com and

American Thinker. The Washignton Post left out what I thought were some extremely important speeches, but I think their list was more geared to MLK day. There are a couple of things that all great speeches have in common:

1.) The moment. The exact time in history where the speakers words will resonate.

2.) The backdrop. The place the speech is delivered amplifies its meaning.

3.) The words. All great speeches are as inspiring when read as they are when delivered orally.

Here's my list (in no particular order):

1. Lincoln’s Second Inaugural

On March 4, 1865 the Civil War was finally winding down. Abraham Lincoln stood on the Capitol steps underneath the recently completed dome – a symbol of the country’s commitment to the Union.

Lincoln delivered one of the shortest but one of the most memorable inaugural addresses of all time. The peroration haunts us to this day:

Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether’.

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Standing 15 feet away from Lincoln was John Wilkes Booth. The two would meet a month later in Ford’s Theater.

2. Patrick Henry “Give me liberty or give me death.”

On March 23, 1775, the British were occupying Boston and had declared martial law throughout the colony. A rabble rousing firebrand member of the House of Burgess named Patrick Henry stood up and, some believe, helped start a war. Others say he gave America a national consciousness that day. What he did was convince some very influential people – George Washington among them – that if the British could take away the rights of New Englanders they could do it to Virginians.

Henry’s bombastic, sneering, inspiring speech was a catalyst for Virgina to support Massachusetts and thus start the country down the road to independence. The peroration from Henry’s speech is what we most remember:

It is in vain, sir, to extenuate the matter. Gentlemen may cry, “Peace! Peace!”—but there is no peace. The war is actually begun! The next gale that sweeps from the north will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! Our brethren are already in the field! Why stand we here idle? What is it that gentlemen wish? What would they have? Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? Forbid it, Almighty God! I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death!

3. Washington’s Speech before Congress Resigning his Commission

It was an act that stunned the Europeans and caused them to elevate Washington to hero status. A winning general simply resigning and going home? Such a thing had never been done – going all the way back to the Romans.

Washington, ever cognizant of his place in history and knowing full well what his self-abnegation would mean to the history books, nevertheless was quite sincere about going home. On December 23, 1783, he stood before Congress and with trembling hands, delivered a short, graceful speech that assured the strength of civilian rule and democracy in America:

Having now finished the work assigned me, I retire from the great theatre of Action; and bidding an Affectionate farewell to this August body under whose orders I have so long acted, I here offer my Commission, and take my leave of all the employments of public life.

4. Franklin Roosevelt’s First Inaugural Address

March 4, 1933 saw the American experiment in ruins. More than 13 million unemployed. Industrial capacity at 50% of what it was pre-stock market crash. Banks closing, soup lines, suicides up – people had lost faith.

Franklin Roosevelt didn’t change things immediately. Indeed, unemployment was still at 10% more than 8 years later on December 7, 1941. But what Roosevelt offered was hope that things were going to get better. And for a people as optimistic as Americans historically are, that’s all that was needed.

Contrasted with the do-nothing Hoover administration, Roosevelt’s activism was a tonic that got America out of the doldrums and blunted much of the impetus for a communist revolution that in 1932 seemed a possibility. Here’s the passage everyone remembers:

So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and of vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory. And I am convinced that you will again give that support to leadership in these critical days.

But it is his peroration that inspires:

We do not distrust the future of essential democracy. The people of the United States have not failed. In their need they have registered a mandate that they want direct, vigorous action. They have asked for discipline and direction under leadership. They have made me the present instrument of their wishes. In the spirit of the gift I take it.

In this dedication of a Nation we humbly ask the blessing of God. May He protect each and every one of us. May He guide me in the days to come.

5. Ronald Reagan at Point du Hoc

This speech is consistently ranked in the top 10 of the greatest of the 20th Century. And for good reason. It has all the elements I mentioned above that makes a great speech plus the drama of having the survivors of D-Day present to listen to it.

The Rangers looked up and saw the enemy soldiers—the edge of the cliffs shooting down at them with machineguns and throwing grenades. And the American Rangers began to climb. They shot rope ladders over the face of these cliffs and began to pull themselves up. When one Ranger fell, another would take his place. When one rope was cut, a Ranger would grab another and begin his climb again. They climbed, shot back, and held their footing. Soon, one by one, the Rangers pulled themselves over the top, and in seizing the firm land at the top of these cliffs, they began to seize back the continent of Europe. Two hundred and twenty-five came here. After 2 days of fighting, only 90 could still bear arms.

Behind me is a memorial that symbolizes the Ranger daggers that were thrust into the top of these cliffs. And before me are the men who put them there.

These are the boys of Pointe du Hoc. These are the men who took the cliffs. These are the champions who helped free a continent. These are the heroes who helped end a war.

Gentlemen, I look at you and I think of the words of Stephen Spender’s poem. You are men who in your ``lives fought for life . . . and left the vivid air signed with your honor.’‘

Video here. MP3 here.

6. Roosevelt Declaration of War Against Japan

In a voice shaking with emotion and indignation, Roosevelt threw down the gauntlet to the Japanese empire:

Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its government and its emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific.

Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American island of Oahu, the Japanese ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack.

Given before a joint session of Congress while men were still trapped below decks in many of the ships bombed at Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt’s peroration drew the loudest and most prolonged standing ovation of his career:

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger.

With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph—so help us God.

I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7th, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese empire.

Roosevelt’s words awoke the “Sleeping Giant” by putting the war in terms of a crusade against the Japanese.

MP3 here.

7. Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address

He was invited as an after thought. The great orator of the time Edward Everett was slated to give the dedication with Lincoln invited to make a “few appropriate remarks.” Originally scheduled for September 23, 1863, Horton said he could hardly do justice to the event with such short notice. The organizers rescheduled for November 19th.

Everett’s two hour oration held the audience spellbound. It was a classic 19th century eulogy with allusions to the Greeks and the Romans, biblical quotes, and flowery language – all given in a booming voice so that all could hear.

Then the President of the United States rose and in his high pitched, tinny, nasally voice, spoke the words that redefined America for all time by greatly expanding the very definition of freedom:

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

No other speech in American history has accomplished so much by saying so little.

8. Kennedy Inaugural

Many historians believe that the January 20, 1961 Kennedy Inaugural address was the best of all time. I agree. The speech is a masterpiece of writing and Kennedy delivered it magnificently.

Beyond that, it was the time the speech was given that gave it such resonance. World War II vets were moving into positions of authority in business, in labor, in politics. The torch was indeed being passed to a new generation. And most Americans believed that the coming years would see a confrontation with the Soviet Union.

But little noticed by many is that the “young people” who flocked to Kennedy’s banner were not baby boomers. That group was too young. Rather it was the “tweeners” who were born between 1935 and 1945 who were too young for World War II and mostly too young for Korea (the Korean war ended in 1953) who supported him. The baby boomers adopted him after his death for the most part.

But Kennedy’s apparent youthfulness – something he cultivated religiously despite his poor health – inspired the entire population. His enthusiasm or “vigor” also was contagious. After the Eisenhower years, it was like the country woke up from a long nap.

The speech was a challenge to the country and to the Soviets. Reading it, one is struck by how bellicose it was – a cold warrior’s dream come true. And its stirring call to sacrifice for the common good – so often misused by Democrats when they call upon the people to help the poor or pay more in taxes – was actually an echo of the kind of sacrifice the country made during WWII.

In the long history of the world, only a few generations have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I do not shrink from this responsibility—I welcome it. I do not believe that any of us would exchange places with any other people or any other generation. The energy, the faith, the devotion which we bring to this endeavor will light our country and all who serve it. And the glow from that fire can truly light the world.

And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.

My fellow citizens of the world, ask not what America will do for you, but what together we can do for the freedom of man.

Kennedy is referring to the coming confrontation with the Soviets – that he makes quite clear he wishes to avoid but has no illusions about the enemy. Echoes of this speech are still heard today making it a truly historic speech.

Video here.

Some of my friends and family are really into American Idol. I'm not really into it other than singing a few songs on my American Idol Karaoke video game for the Sony Playstation 2. However, the "real," first American idol was Elvis Presley, aka "The King." He’s been dead for 30 years, but Elvis Presley through his estate earns millions more than he did when he was alive. New generations of young people continue to be fascinated by the man whose wiggling hips were once censored on TV and whose voice offered something special to listeners. Born in a simple shotgun house in

Some of my friends and family are really into American Idol. I'm not really into it other than singing a few songs on my American Idol Karaoke video game for the Sony Playstation 2. However, the "real," first American idol was Elvis Presley, aka "The King." He’s been dead for 30 years, but Elvis Presley through his estate earns millions more than he did when he was alive. New generations of young people continue to be fascinated by the man whose wiggling hips were once censored on TV and whose voice offered something special to listeners. Born in a simple shotgun house in  Here's something else interesting about Elvis:

Here's something else interesting about Elvis:_Movie_Poster.jpg)

.svg.png)